GEORGE HORNIDGE

Russelstown House in the 19th Century was in a most attractive location. The impressive Russborough House was close by, the river Liffey meandered along the valley, beech trees and others abounded and on to Poulaphouca you had the Falls, a lovely place for a picnic on a good day. You could also take a jaunt down Featherbed Lane, past Tulfarris and on to the Seven Churches (Glendalough). The Kildare Hunt was enjoyed by locals and quality alike. There were fox coverts at Elverstown, Downshire, Baltiboys and elsewhere. In fact West Wicklow was excellent hunting country. Poor Tom Hornidge and his brother George, sons of Cuthbert Hornidge most certainly had a privileged upbringing. But as younger sons they had to fend for themselves with assistance from the Russelstown estate.

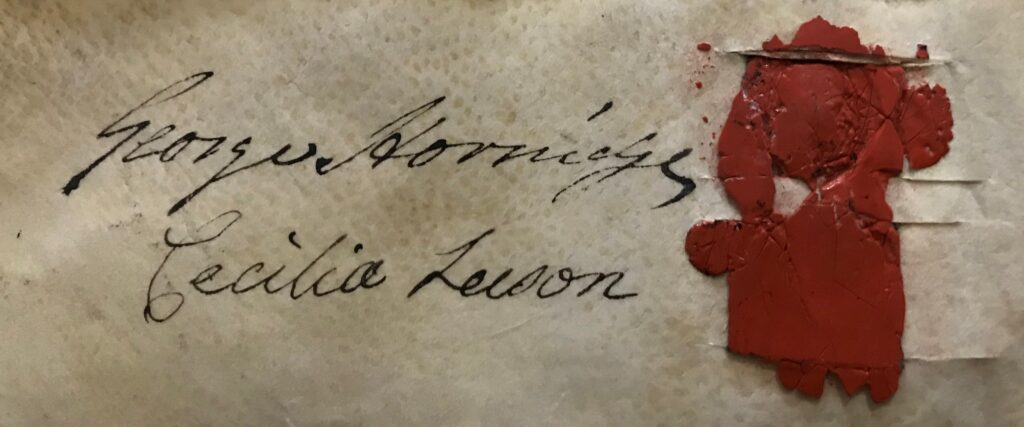

For some years Cecilia Leeson, daughter of barrister John Leeson and granddaughter of Brice Leeson, 3rd Earl of Milltown had been visiting her father’s old home at nearby Russborough House. Cecelia got to know George Hornidge of Russelstown and, in what looked like a good match, they were wed in the year 1820. Her marriage settlement shows clearly that they had a good start to their lives together. George had joined the army and rose eventually to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the service of the British Crown. Sadly, the bridal path ahead was not strewn with roses.

For an idea of the kind of lives led by army officers in the 18th and early 19th Century we are indebted to the author Charles Lever and his novel “Charles O’Malley the Irish Dragoon”. In it the fictional O’Malley leaves Galway with his “man”, Mickey Free and with his comrades is involved in a continuous spree of riotous living. A “man’s” duty among other things was to carry his master on his back from the army mess to his quarters when in his cups, in other words when blind drunk. The lives they led were both exciting in times of action and boring in peacetime when they had too much time on their hands. They travel from Dublin to Lisbon by sea and as they pass the Old Head of Kinsale Mickey gets a bout of nostalgia, which inspires O’Malley to humorous verse as follows:

Then, fare thee well, ould Erin dear;

To part–my heart doth ache well.

From Carrickfergus to Cape Clear,

I’ll never see your aequal.

And, though to foreign parts we’re bound,

Where cannibals may ate us,

We’ll ne’er forget the holy ground

Of poteen and potatoes.

When good St. Patrick banished frogs,

And shook them from his garment,

He never thought we’d go abroad,

To live upon such varmint;

Nor quit the land where whiskey grew,

To wear King George’s button,

Take vinegar for mountain dew,

And toads for mountain mutton.

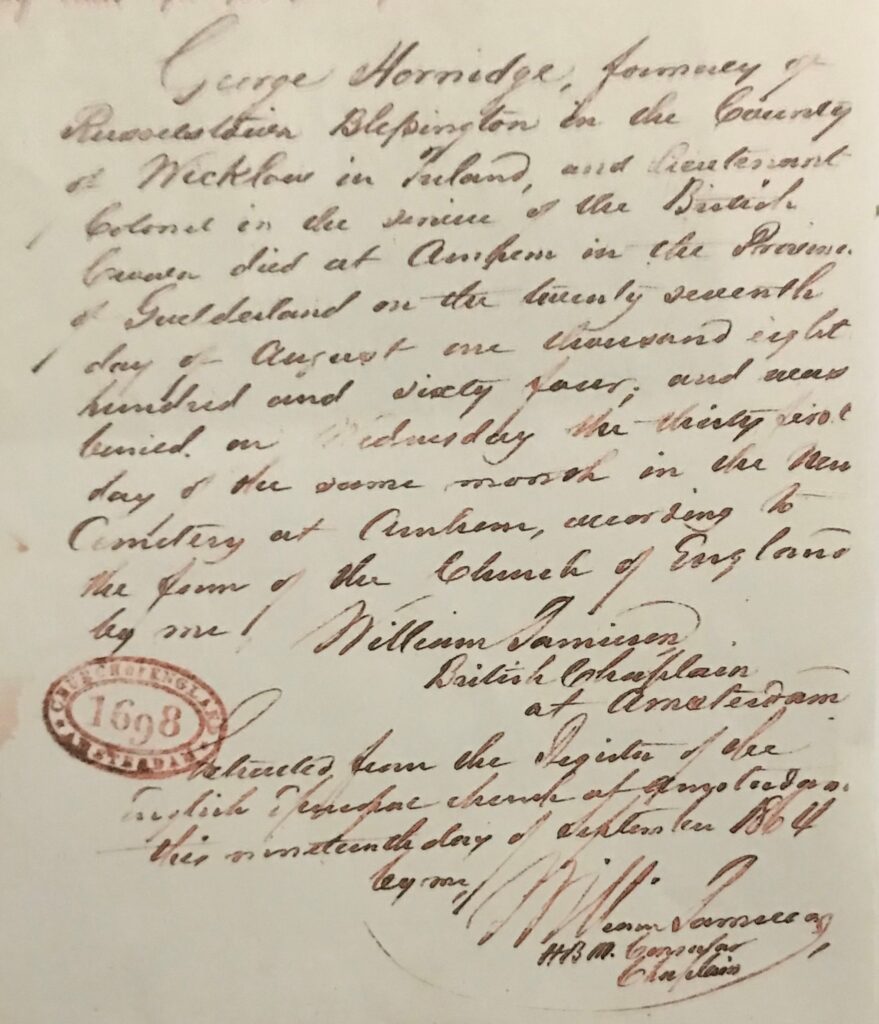

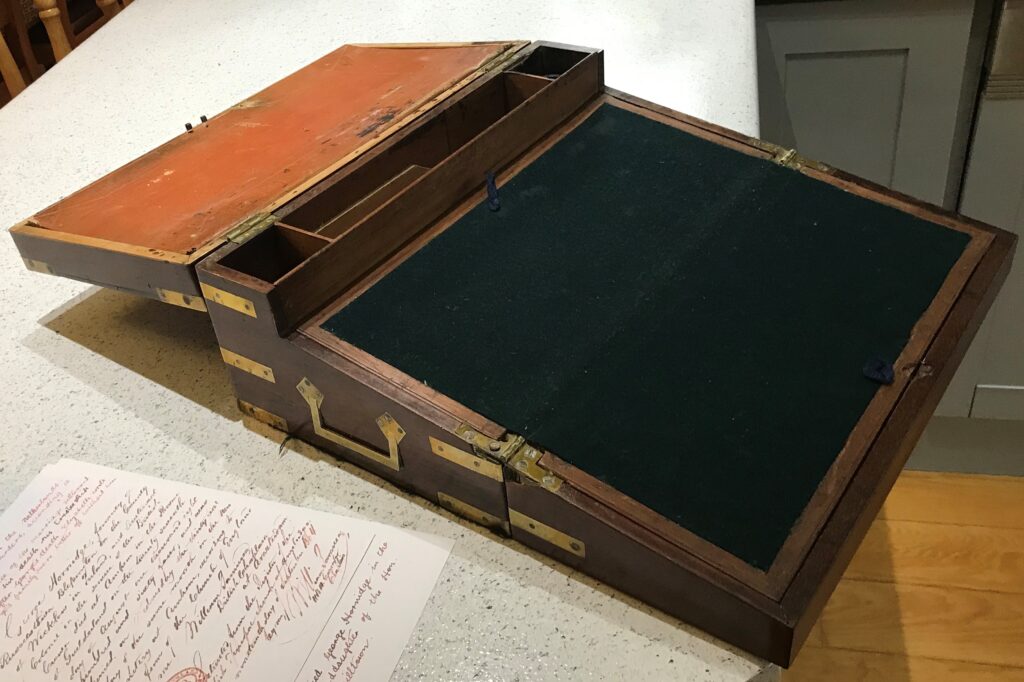

The next we hear of George is from the diary of Mrs Smith of Baltiboys. She had been a trustee of George’s estate and was involved in the settling of his affairs when he passed away in 1864. He had died in prison in Arnhem, Holland, where he had been incarcerated for a second murder. The circumstances of the crime we know not, or indeed whether he was still in the army at the time. Mrs Smith’s caustic comment was that his wife and children were better off without him and that she was glad to be rid of the responsibility of settling his affairs. Henry Smith had been a trustee of the Marriage Settlement back in 1820, and when he died Elizabeth took over his role. The marriage settlement is extant as is a letter from the British chaplain in Arnhem confirming the date and place of his burial.

THOMAS HORNIDGE

This is Black Sheep No. 2.

Tom ended up in a house in South Circular Road in a state of destitution. His brother, John Hornidge, the Russelstown Estate owner had died in the year 1847 at the height of the Irish famine. Because of the uncertain times and the attacks on landlords he had carried a loaded pistol at all times. Getting down from his carriage he accidently discharged it, the ball entering his leg. Surgeon Porter was sent for, post haste, to Dublin. Porter came immediately, operated and removed the ball and as much of the trouser cloth as he could. But in those days they did not even sterilise the scalpel so it was inevitable that infection would set in. John gradually worsened and a week later he died. In his will he had left legacies and annuities to all his family. Why Tom fared worst of all his siblings is perhaps indicative of the man himself. He was to get £52 per annum, or £1 per week. This money would be paid through the family solicitors, Cathcart & Hemphill, in Dublin. Along the way Tom had gotten married and had a daughter. We hear through his nephew John James Hornidge the later owner of Russelstown that Tom had spent some time in the Marshalsea in Dublin. This was a debtors’ prison where people were held until debts were settled or until any hope of payment had ended, as the plaintiff was responsible for feeding the inmate. Because of Tom being declared a bankrupt the annuity could have been voided but family would not go that far. While in the Marshalsea nephew John had bought Tom a suit and he was going to deduct the cost from the annuity, sticking to the letter of the law. During the 1870’s a series of letters were written by Tom or, on his behalf, by a Mrs Quigley probably his landlady, to the Hornidge solicitors pleading for payment, sometimes in advance. Nephew John had been giving him a bonus of £1 every Christmas and this had to be asked for every year. I quote one of these pathetic letters:

South Circular Road,

Dear Sir, 9th Jany ’74.

What money you gave

yesterday, only paid up to the

8th inst, and as Mrs Quigley tells

me Mr John Hornidge left

something for me for Xmas. I

must ask you for mercy sake to

let me have it as I am in the

greatest of want.

Yours Truly,

T Hornidge.

G. Cathcart Esqr.

“What a falling off was there”, as Shakespeare commented once. To be born into such wealth and to end up thus. The letters cease in the year 1879, signifying maybe the end of Tom’s life as well.

Was he interred in Blessington? There certainly is no burial recorded in St. Mary’s Register. Did he end up in a pauper’s unmarked grave? Family loyalty had limitations perhaps?

Any comments or questions would be welcome: To contact Jim Corley please click here