When the Ordnance Survey was being carried out in Ireland in the 1830’s a group of historians were given the task of recording the antiquities in the different localities. There were only four of them for all Ireland, so it was to be a great undertaking for so few. They covered a lot of ground in a short time. Their travels were arduous especially in Winter, remembering that the climate was much more extreme in those days, and clothing and footwear were more basic. They wrote letters back to headquarters in the Phoenix Park, letters which are now available to researchers.

This article deals with one such letter written by John O’Donovan on January 7th 1839. He and O’Connor had tried to get a car to take them from Blessington to Glendalough but the Hotel Keeper was charging too much so, next morning, they headed off themselves on foot, a mere 16 (Irish) miles to their destination. All went well until they reached the side of Cross Mountain and I quote from the letter :

Pic 2: Burgage to Baltiboys unless one can walk on water or hire a boat go down N81 and turn off for Valleymount where you will pick up the old road. A mile beyond Valleymount, instead of turning right go straight on. Before the lake Burgage Bridge would have gotten you across the Liffey.

Pic 3: Cross Mountain. The title Cross or Crosslands referred to land owned by a Bishop

Pic 4: Cross on rock, now much eroded

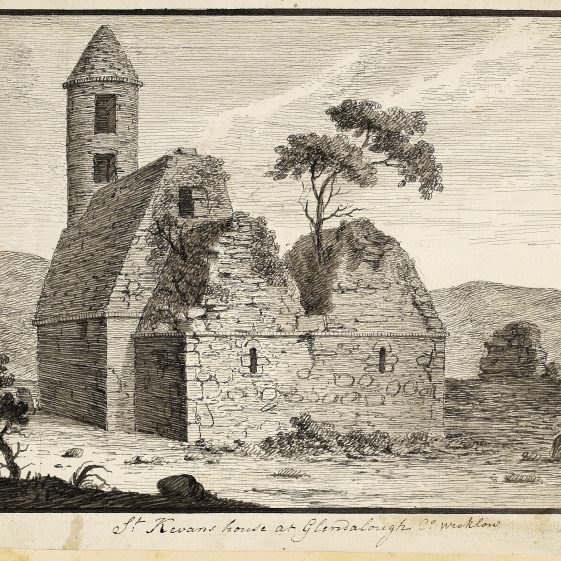

Pic 5: St. Kevins, one of he seven Churches of Glendalough, 1779, by, it is thought, Bigari.

Pic 6: Glendalough by George Petrie.

Note : all the letters for co Wicklow are available in a publication entitled “The Ordnance Survey Letters…Wicklow”.

“…before we reached the top of the mountain we found ourselves in the middle of a snow storm. I stopped short and paused to consider what to do. The clouds closed around us and the wind blew in a most furious manner. Here we met a countryman who told us that the distance to Glendalough was 9 miles, that the road for 6 miles was uninhabited, and that the last flood had swept away 2 of the bridges. I got a good deal alarmed at finding ourselves a mile and a half into the mountain and no cessation of the snow storm. I told O’Connor, who was determined to go on, that I would return, that I did not wish to throw away my life to no purpose. I returned (coward!) The whole side of the mountain looked like a sheet of paper horribly beautiful ! but the wind was now directly in our face. We returned 3½ miles and stopped at Charley Clarke’s public house, where we got infernally bad treatment. The next morning I felt feverish from having slept in a damp bed in a horribly cold room, but seeing that the snow began to thaw and it being Sunday I resolved to go on to the Churches. So we set out across the same mountain in which we had been stopped by the snow. I never felt so tired. Sinking thro’ the half dissolved masses of snow and occasionally down to the knees in ruts in the road, which proved exceedingly treacherous as being covered by the snow. One of my shoes gave way and I was afraid that I would be obliged to walk barefooted. We moved on, dipping into the mountain, and when we had travelled about 4 miles we met a curious old man of the name Tom Byrne, who came along with us. We were now within 5 miles of the Glen but a misty rain, truly annoying, dashed constantly in our faces until we arrived at St. Kevin’s Shrine. Horribly beautiful and truly romantic, but not sublime.

Fortunately for us there is now a good, but most unreasonably expensive kind of a hotel in the Glen, and when I entered I procured a pair of woollen stockings and knee breeches, and went at once to look at the churches, which gave me a deal of satisfaction. (I looked like a madman!)

We got a very bad dinner and went to bed at half past twelve. I could not sleep but thinking of what we had to do and dreading a heavy fall of snow which might detain us in the mountain. O’Connor fell asleep at once. At 1 o’clock a most tremendous hurricane commenced which rocked the house beneath us as if it were a ship. Awfully sublime but I was much in dread that the roof would be blown off the house. I attempted to wake O’Connor by shouting to him, but could not. At 2 o’clock the storm became so furious that I jumped up determined to make my way out, but I was no sooner out of bed than the window was dashed in upon the floor and after it a squall mighty as a thunderbolt. I then, fearing that the roof would be blown off at once, pushed out the shutter and closed it as soon as as the direct squall had passed off and placed myself diagonally to prevent the next squall from getting at the roof inside, but the next blast shot me completely out of my position and forced in the shutter. This awoke O’Connor who was kept asleep as if by a halcyon charm. I closed the shutter again despite of the wind, and kept it closed for an hour when I was as cold as ice (being naked all the time!) O’Connor went to alarm the people of the house, but he could find none of them, they being away securing their cattle in the outhouses which were much wrecked by the hurricane. The man of the house at last came up and secured the window by fixing a heavy form against it. I then dressed myself and sat at the kitchen fire till morning. Pity I have not paper to tell the rest. A tree in the Church Yard was prostrated and many cabins in the Glen much injured. The boat of the upper lake was smashed to pieces. The old people assert that this was the greatest storm that raged in the Glen these seventy years.”

Your Obedient Servant,

J. O’Donovan.

Later that night was known as “The Night of the Big Wind.”

Leave a Reply