I had no particular knowledge or interest in the above Paul until one determined lady in Camerillo, Southern California, Patricia Thomas, emailed me almost a year ago. She had found the website I had set up some years back. She had traced her lineage to the above Mr. Carney back to 1848 at Ballydonnell North when he was paid the sum of £50 by his landlord, the Marquis of Downshire, to assist him to the New World, thus vacating his premises at Ballydonnell. This would have compensated Carney for the stock, crops and dunghill he was leaving behind. Landlords wanted to clear their lands of tenants who could not pay their rents after the failure of the potato crop. In fact they wanted to be rid of all their smaller tenants. Also, a Hunting Lodge was planned for nearby Ballylow; so tenants were to be replaced by grouse, woodcock and hare.

With the said Paul Carney went his wife Ann (Doyle) Carney and 8 children. Patricia had located the ship on which they sailed, and in the depth of Winter, the month of November. They embarked at the Port of Dublin and headed off for America the land of hope. Paul had signed his name on a document in 1846 with a flourish, suggesting he had some level of literacy, perhaps gleaned from the nearby hedge school at Lacken . There was a great thirst for knowledge and book learning among rural Irish people at the time. Parents saw schooling as a way of advancement and were only too willing to invest their few shillings in the pursuit of education. Often they paid in kind with loads of turf or sticks, bags of spuds or turnips or a bottle or two of the local fire-water. A few days’ labour on the schoolmaster’s potato patch or turf bank would help.

The people admired a master who could take his drink. They thought the alcohol inspired him to greater heights of eloquence and logic. If the school was lucky to have a good teacher then the students would reach a high standard in the three ‘rs’, reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic. Perhaps also surveying.

It is very probable that the Carneys had relations in America who had gone ahead of them. Emigration to the New World had been happening before the Great Famine. Many had left for adventure and for a better life. They often left with a light heart if we believe some of the emigration songs. The chorus of Murcheen Durkin is an example and goes like this:

“So goodbye Murcheen Durkin,

Sure I’m sick and tired of workin’

No more I’ll dig the praties,

No longer I’ll be fooled.

Sure as me name is Carney

I’ll be off to Californey;

Instead of digging praties

I’ll be diggin’ lumps of gold”.

But there were also more sad, emotive songs like

“Shores of Amerikay”, one verse of which was:

“And when I am bidding my last farewell

The tears like rain will fall

To think of my friends in my own native land

And the home I’m leavin’ behind.

But if I should die on a foreign land

And be buried so far, far away

No fond mother’s tears

Will be shed o’er my grave

On the shores of Amerikay.”

Most evocative of bad times was “Old Skibbereen”, a verse of which I quote:

“Oh son I loved my native land with energy and pride.

‘Til a blight came o’er my crops,

My sheep and cattle died.

My rent and taxes were too high;

I could not them redeem.

I heaved a sigh and bade goodbye

To dear old Skibbereen”.

During the Great Famine people left in droves because of utter destitution and being put out of their cabins when they could not pay their rents. Some individual landlords did their best, like the Smith family of nearby Baltiboys House. But imperialism was not a benevolent institution. Lord Palmerston, former Prime Minister, owned the 10,000 acre Classiebawn estate in Co. Sligo, not far from my home town of Dromahair. Palmerston offloaded over 2,000 of his evicted tenants on 9 ships from Sligo port to Canada during 1947. They arrived there in a pitiful condition, half naked and totally destitute.

Patricia, or Pat as she likes to be called, found the manifest of the ship the Carney family sailed in and sent me a copy of it. The details it contains are as follows:

The ship, Marianna, arrived in the Port of New York on the 16th January 1849 after 57 days at sea, having left the Port of Dublin on the 20th November 1848. The ship’s burthen was 379 tons; her Captain was W. Crocker.

Details of the family are as follows:

Paul Karney (Father)……………..aged 45.

Ann Karney (Mother)…………… aged 40.

Michael Karney, Eldest Son. aged 21.

Miles Karney, Second Son… aged 19.

Watt Karney, Third Son.…… aged 17.

Mary Karney, 1st Daughter.…aged 15.

Peter Karney, Fourth Son…..aged 13.

Thomas Karney, Fifth Son……aged 6.

Eliza Karney, 2nd Daughter…..aged 4.

- Paul Karney, 6th Son……………Infant.

Many poverty-stricken emigrants crossed over to Liverpool. The fare was affordable and they usually had connections there. Many who sailed to New York remained in New York or in cities nearby. To go west and buy land emigrants needed capital. So how did the Carneys manage. Often those relations who had gone before them would help out. They might pay the fare, or send some money. Neither did they leave Ireland with empty pockets. The Downshire landlord had awarded them £50. This was to compensate them for any valuables they were leaving behind, like crops, and most important the dung hill.

The voyage took 2 months so, while they brought food with them, they would have bought some food on board. Then the journey from New York to Illinois was almost 900 miles. I would like to think that they travelled by covered wagon drawn by oxen or mules, most of the family on foot. But probably not. It was possible to go by water – up the Hudson River to the Erie Canal and on to Lake Erie and through the Great Lakes right up to Lake County. Vast numbers had gone west this way. In Lake County they paid $250 for a 40 acre farm and had to get their farming enterprise off the ground. It all required more money.

Lets look at their 2 main sources of income back home. Good farmers could be surprisingly productive what with being self sufficient in food and fuel. They churned milk from their small black cows. Excess butter was sold. Wool was sold to the Quakers at Baltiboys up until 1798, or afterwards to the Woollen Mills at Ballymore Eustace, where they could get finished cloth in exchange for their wool. Every hill farm would have its own spinning wheel. People would call in of an evening for a ‘ceilidhe’’ a social get-together. The visitor would lend a hand at whatever was going on. Lambs were sold at the Dublin market. The fact that they were not up to date with their rent often indicated only a certain shrewdness in the very clever hill farmer. The ‘rainy day’ was always foremost in his mind. As the saying went:

“they would make a prisoner of every shilling”.

Paul and his sons combined to make an effective workforce and if they were involved in the quarrying business could have gotten some money together. They may have worked for a while in New York before heading west. (Pat thinks this is unlikely). But I think it is almost certain that their forerunners did sojourn in New York, where work was plentiful and well paid, before they set off for Lake County. The Carney family would have learned much from those who had gone before them and would in general have followed in their footsteps.

We await more information as to how the family prospered in Lake County. Was there employment there for the four Carney men apart from their farming enterprise?

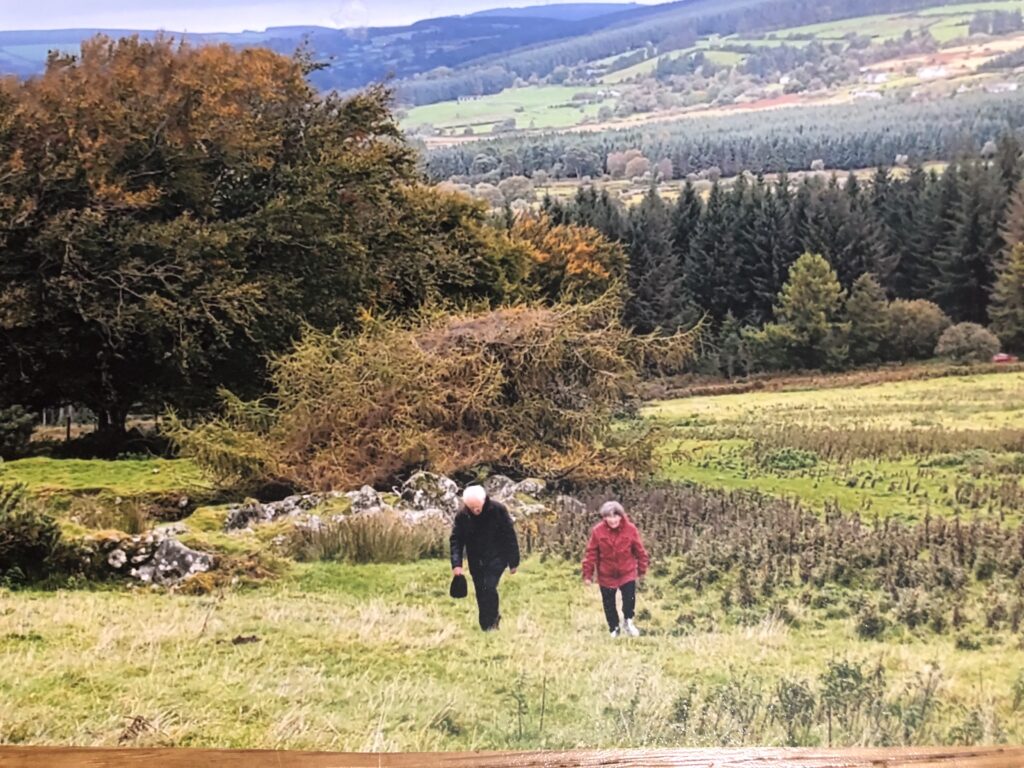

I have been looking at the remains of an old clochan at Ballydonnell North. Thankfully, An Coillte, (the state owned forestry company) have not planted trees over it. Cloch means stone in Irish, and a clochan is a small number of stone houses and buildings, dating back to later mediaeval times. Together their dwellers farmed their land and protected themselves and their stock from intruders. The Carney family or some of their kin may have lived there.

Pat and I are in a quandary as to whether the Carney family over-wintered in New York – all waterways would have been frozen over in January 1849.

The Carneys were very supportive of the rebels of 1798, when the native Irish made a bid for freedom from an oppressive empire. The rebel leader General Michael Holt in his memoirs makes a mention of calling to Michael Carney of Ballydaniel where he was well received; then on to Ballylow to visit more of his supporters. Their landlord, Finnemore, suspected a certain young fellow of plundering some of his property, but did nothing about it because this boy had relations up in the mountains.

Any comments or questions would be welcome: To contact Jim Corley please click here