The marriage of Lieut. Col. Henry Smith formerly of Baltiboys and now a soldier of the Honourable East India Company, and his bride Elizabeth Grant of Rothiemurchus in Scotland took place in Bombay Cathedral on June 5th 1829. It was a marriage of convenience in that Henry, being a second son had no great inheritance, and was at death’s door because of chronic and acute asthma. The climate did not suit him. Add to that that he was 17 years older than his wife to be. In fact he was just about hanging on to life by the proverbial thread and was, most definitely, no great catch. Still, he was an officer and a gentleman and was a suitable prospect for a maturing lady with little or no dowry. Such was Elizabeth’s predicament. Being a realist she recognised her situation and, vowing to make the best of things, she gladly entered the state of matrimony. She would make every effort to have a successful marriage, and while she was not madly in love with Henry, she did like him and he had a kind and easygoing nature. As it turned out the marriage lasted the test of time, and Henry lived into a ripe old age.

Some days before the marriage was solemnised news came that Henry’s brother John had died, without issue, in Paris and Henry was now master of the estate at Baltiboys.

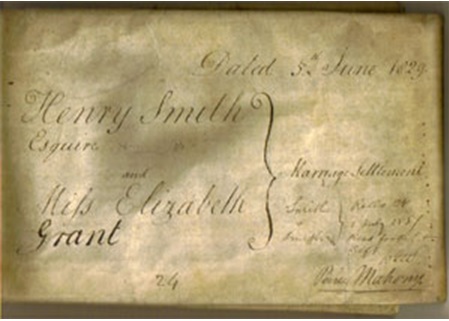

Well before that, however, a marriage agreement had been drawn up between the couple. It should be kept in mind that even in the event of Henry’s death the estate in Co. Wicklow could never be owned by Elizabeth, but would be held in trust by trustees. A son or daughter would be heir to the property, and in the event of no children the estate would pass to the nearest male relation. In the possibility, indeed probability, of the demise of her husband, Elizabeth would be well looked after. She would get an annuity of £230. She would have an entitlement from the Military Fund of the East India Company. A sum of £4,000 would be provided for any children of the union. A further £6,000 would become available on her own death. Sums of £4,000 and £3,000 were to be immediately directed to the trustees. Provision for the maintenance and education was arranged for any boys till the age of 21 and girls also to 21 or until they married. If Henry were to expire in India Elizabeth was to be paid 8,000 rupees to provide passage to England and she would be left all household furniture, jewels, plate, books, linen, china, uisce (whiskey), and other liquors. £6,000 had been secured on the lands of Kinloss in Scotland by Elizabeth’s father Sir John Peter Grant to the three younger children of his marriage, of whom Elizabeth was one.

In those days settlements were drawn up on vellum because of its durability, and even to-day, after the greater part of two centuries, the document is in excellent condition. It comprises 5 large sheets and is signed and sealed by the following:

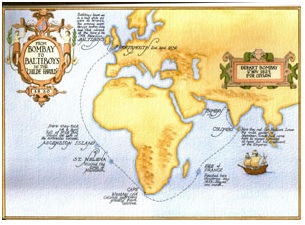

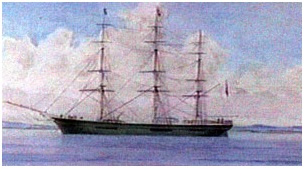

Henry Smith, Elizabeth Grant, J. P. Grant (father), W.P. Grant (brother), Archibold Robertson, J.E Craig and E. Ironside. The several witnesses were members of the Bombay Judiciary, of the Bombay Civil Service, or of the east India Company. The trustees would be: Sir John Peter Grant, Archibold Robertson, Richard Hornidge of Tulfarris, William Patrick Grant, James Gibson Craig and Edward Ironside. This agreement would regulate their affairs as long as they both should live. While still in their first year of wedded life, they were advised by their doctor that if husband Henry were to remain in the oppressive climate of India in the pursuit of his career, he faced certain death in the not too distant future. A decision was made, therefore, to return to the more suitable climate of Europe and, in particular, Baltiboys. So it was that on the 4th of November 1829 they headed for home in a sailing ship, the Childe Harold, a new swift vessel beautifully fitted up, commanded by Captain West, an old experienced lieutenant in the Royal Navy. Among their luggage was a good supply of books, food, wine, medicine and, I would imagine, their marriage settlement, and any other legal documents. The Colonel had engaged a native male attendant, as when a violent fit of asthma attacked him he was totally helpless.

Their first port of call was Colombo in Ceylon. Here they were welcomed by the Governor and lavishly entertained. Travelling gentry were always in demand as they brought news with them, they discussed and gossiped well into the long nights, they partied and enjoyed each other’s company, and, as nobody was in any particular hurry, they stayed for a month. One of the other guests at Government house was Sir Hudson Lowe, former Governor of St. Helena while Napoleon was incarcerated there. It would appear he had been over officious in carrying out his responsibilities towards his prisoner, and when the English public got to know of his meanness he was vilified to such lengths that he retreated into oblivion. Next stopover was the Isle of France, which they reached on Christmas morning, and where they spent another month before once more taking to the open seas. The weather got colder as Table Mountain came in sight. Here at the Cape they got rid of the cow they had on board since India – she had been but a poor milker. Instead they took on two goats which were not much better. And so on to St. Helena. The colonel was in a very poor state at this time and there were fears for his survival. They visited the tomb of the great Napoleon Buonaparte. Mrs Smith does justice to her feelings on the occasion, and it is worth quoting her few sentences from The Highland Lady in this regard: “The tomb was saddening; ‘after life’s fitful fever’ to see this stranger grave; in a hollow, a square iron railing on a low wall enclosed the stone trap entrance to a vault, forget-me-nots were scattered on the sod around, and the weeping willow drooped over the flag. The ocean filled the distance. It would have been better to have left him there, with the whole island for his monument.” At Ascension Island they took on two goats “full of milk”, and the Highland Lady asserted later that it was the milk of these animals that saved the life of her asthmatic Colonel over the rest of the voyage. The gallant little sailing ship reached Portsmouth at the end of April 1830. Since they had departed Bombay almost five months had passed. The Colonel had picked up somewhat and was able to make his own way ashore.

A few weeks later they arrived in Ireland. Baltiboys House was in a bad state as were its tenants. The previous owner, Henry’s brother John, had fled abroad at the time of the 1798 rebellion. The estate had been neglected. Within a short time plans were drawn up for a new house (these plans are still extant ). The tenants’ lot was improved. They had some employment in building the new mansion, and later on draining their farms. Thousands of trees were sown. An effort was made to do away with small uneconomical holdings, without raising too many hackles. When the potatoes rotted in the mid 1840’s the Smiths were not found wanting in their efforts to relieve their hungry tenants. They set up a soup kitchen for their needy tenants and former tenants or workmen who had a moral claim for assistance.

Remember the all important Marriage Settlement made in Bombay in 1829? Well, it was still a binding legal document and came into unexpected prominence many years later. On Henry Smith’s death their only son, Jack, inherited the house and estate at Baltiboys. Jack had married in June 1871 to Frances Harvey, (a relation of the Capt. Harvey R. N. who fought alongside the great Nelson), but died a mere 2 years and 5 months later. Two months after his death his little girl Elizabeth was born. Because Jack had made no will in favour of his mother this baby was now owner of the house and estate. Her grandmother was just a tenant where for 40 years she had held sway. Without her knowledge there had been an auction of her property. All her fine cows were gone. As were her pigs and poultry, horses and carts, implements, beehives, frames, plants from greenhouse, tubs and watering pots and so on. All had belonged to her son Capt. Smith. The scandal of an auction could have been prevented by John J. Hornidge of Russelstown, she felt, but he was bent on doing his utmost for the young widow and orphan child, and the deed was done before she knew of it. Mr Hornidge then tried to sell the house furniture. The Smith solicitor, Mr Cathcart, was contacted to see if this auction could be stopped. Mr Cathcart came down with the Marriage Settlement made in India in 1829. He pointed out the part that stated that in the event of Henry Smith’s death all furniture, plate et cetera would go to his wife Elizabeth. The plans for auction were abandoned. The Highland Lady continued to live at Baltiboys. She purchased a horse and cart, 2 wheelbarrows, spades, rakes, a shovel, plough, harrow, cow, pig, 6 hens, 3 Aylesbury ducks, and had work on her hands for many a year to come. Her jointure paid the rent on Baltiboys and she took in grazing cattle to pay the workmen and housemaids. Her daughter-in-law Frances was very kind to her and had not allowed her brougham to be sold nor the double harness Jack had given her for it. Frances herself had to buy Jack’s watch, rings, pictures, books, sword and so on. Such was the law.

Aunt Bourne died in the year 1867 and left most of her estate to Mrs Smith. Her share came to more than £30,000, with which she released her family from liabilities, lent £10,000 to the Bermingham estate in Tuam, Co. Galway, at five and a half % per annum, purchased the townland of Lacken, also land at Golden Hill. Later on her daughter Annie and her 10 children came to live at Baltiboys.

Any comments or feedback would be welcome: To contact Jim Corley please click here.

Maggie Saunders

How very interesting. I have just been handed some correspondence from Louise Verity, Elizabeth Smith’s great grand-daughter, whom I gather is illustrating a new edition of the Irish Journals. So I have come across your article in doing a little background reading. Would you have any information on her issue which would continue the story of the family down to the present day?