Tulfarris History

A long time since this Fergus built his mound, or perhaps others built it to mark his interment here. It could have been a sacred place where druids danced and carried out their rituals. It could have offered protection or shelter. It was on an elevated site so enemies could be spotted far off. If only we could know. But we hear that a minor dig was carried out on the Tulach some years ago and that bones were found. What else is down there? Perhaps one day the mound will be fully excavated. People through the ages have had a reverence for ancient places and so it has survived, despite the comers and goers, despite wars, rebellions and all sorts of changes in land use and ownership. It was not disturbed during the era of land reclamation, or of the building of Tulfarris Golf Course.

The Hornidge family had lived at Tulfarris for two and a half centuries, yet all that reminds us of their sojourn here is the letter ‘H’ on the gate leading to the original walled garden.

The house we know today was built or started off about the year 1740 by one of the Richard Hornidges of Tulfarris, the porch being added on in Victorian times perhaps around 1850.

The year of Rebellion, 1798, was a dreadful time in West Wicklow. Poverty stricken and disgruntled tenants rose up against people like the Hornidges. Many houses were looted and burned: crops, fodder, cattle robbed or destroyed. The gentry and their supporters organised their own defence in conjunction with the Government. Major Richard Hornidge of Tulfarris was in charge of the Lower Talbotstown Cavalry and, we suppose, may have engaged the rebels. At full strength his corps consisted of 34 mounted men and 60 infantry, made up of Protestant farmers and gentry and their sons. Naturally there had been animosity between the new owners of the land and those who had been dispossessed, especially since Cromwell’s time.

For a few Summer months General Holt and his rebel troops moved around this area up as far as the Wicklow Gap and down to the Glen of Imaal attacking the enemy and retreating as strategy demanded. From a base at Oakwood, off the Wicklow gap he raided Blessington appropriating, according to his Memoirs, 150 sheep, 32 cows and bullocks, and 10 horses, one a beautiful 3/4 bred mare belonging to parson Benson. The government compensated loyal property owners for damage caused during the rebellion, Richard Hornidge receiving the sum of £2,085-14-9 for the losses he suffered at his residence. These included cattle, furniture, wine and loss of pasture. Settlements were generous. There is no reference in the claim to any burning of the house. After Holt’s surrender, the famous rebel , Michael Dwyer, continued to harass the Govt. forces for many years to come. People like him kept alive the spirit of freedom that, it was hoped, would be won one day. Landowners of doubtful loyalty to the Crown such as the Leesons of Russborough or John Smith of Baltiboys got no compensation. Major Hornidge lived on until the year 1840, aged 76, and his burial is recorded in the Church of Ireland register in Blessington.

West Wicklow was a popular place for fox hunting and was much frequented by the Kildare Hunt Club founded in 1804. Major Hornidge had been an original member. Close by was the renowned fox covert at Baltiboys. Hunting was one of the few activities when landlords and their tenants worked together in chasing the fox. Good horses and good horsemanship were revered by high and low.

The next Richard Hornidge (son of the Major) was the owner of Tulfarris during the Famine years 1845 to 1850. We know from the diaries of Elizabeth Smith of Baltiboys that Tulfarris looked after its starving dependents as best they could. Even so some people ended up in the Naas Workhouse and the general population would continue to be poor and miserable for many years to come. We may ask why there was such poverty in the country even before the famine. The fact is the whole system of land tenure ensured that the higher echelons of society which included landlords, strong farmers, professionals, both sets of clergy, especially the Protestant clergy with their tithes, and politicians had all the privileges and wealth; there was little left for the over populated lower classes. Even when individual landlords were good, landlordism was not. Those landlords who lived debauched lives, took little interest in estate matters and ran up debts, left a trail of disaster after them. Those who fed their dependants in famine times sometimes went broke.

When you can identify the recipient of the medal and his abode it increases greatly the interest therein. Such is the case with the Tulfarris medals above. Richard Joseph Hornidge the next owner but one of Tulfarris was born in the year 1863. We have more in the way of records about this man than previous Hornidges. We have, for instance an entry from Ellis Island of him and his family passing through in the year 1893. They were bound for Virginia and their stay would be protracted. Reason for going there was that Mrs Hornidge’s mother lived in Albemarle, Virginia. The members were as follows:

Richard Joseph aged 30,

Mrs Hornidge aged 25,

Edward aged 32,

Robert aged 6 and

Phoebe aged 2.

They had travelled on the ‘Furnesia’ out of Glasgow via Moville Co Donegal. The Hornidge family, like most of the gentry travelled a lot in Ireland and on the Continent, often renting out their houses for a year or more.

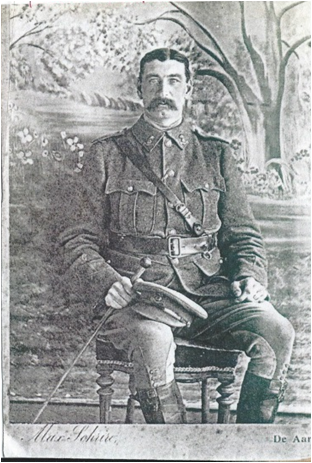

The year 1900 was a memorable year for Richard Joseph. We see him as captain of Naas Golf Club and also on his way to South Africa, this time a Captain in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, to take part in the Boer War. This war was regarded by many of the hot blooded gentry as more of an adventure, a good hunt. Instead of hunting foxes or pig-sticking they would have fun with those boorish Dutchmen who had dared defy the Empire. They would have to be taught a lesson. It soon became evident that it wasn’t going to be a stroll in the park and the upper class suffered serious casualties down there, more from disease than from actual fighting. The great disappointment was that they couldn’t set up a decent cavalry charge. They had brought their hunters with them as they steamed south only to use them for getting around, as the conflict developed into trench warfare and Boer ambushes. Many horses died from tsetse fly infection. The Walmer Castle departed South Africa for England on August 27th 1902 with Capt. R. J. Hornidge on board. At least two other members of the local gentry had served in South Africa, they being Capt. Thomas Stannus of Baltiboys and Capt. Maude of Tinode.

This medal has a youthful looking Queen Victoria on one side and on the reverse the mythological Britannia encouraging her troops as they trample on the enemy Boers.

In the year 1909 Richard Joseph and family are on their way again to Ellis Island and Virginia to visit Mrs Hornidge’s mother. This time their ship was the Coronia, carrying 1,500 passengers, out of Liverpool. A new regulation stipulated that entrants to the U.S. had to have at least $50 each. Details of their appearances were noted.

Richard J. was over 6’- 4” in height, his complexion was dark, hair brown, eyes blue, born in Blessington;

Mrs Hornidge was 5’- 0”, had a fair complexion, fair hair and blue eyes, born in Limerick;

Phoebe was 5’-3” tall with fresh complexion, fair hair, blue eyes and born in Blessington.

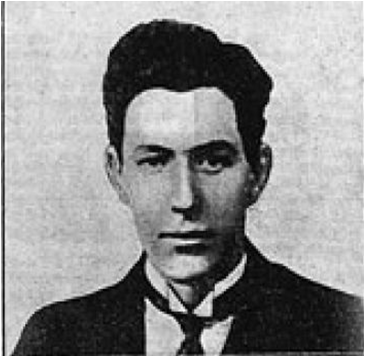

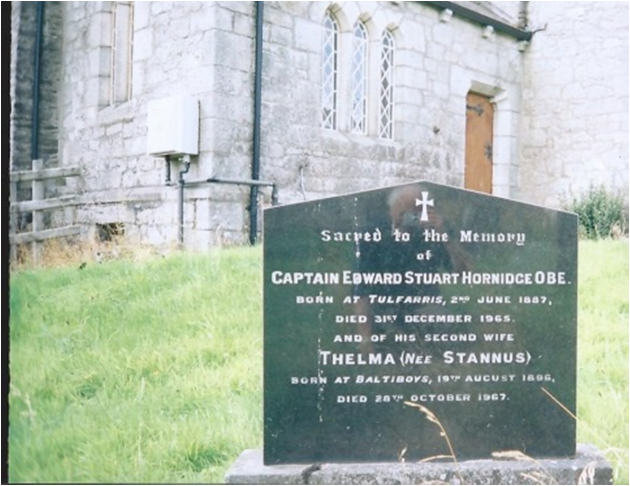

Richard Joseph died in the year 1911, aged a mere 48 years. His heir was his son Edward Stuart (born 1887) who was at the time in Australia. Edward had attended Cambridge University with sporting distinction in that he had rowed for Cambridge’s first team. Finishing college he signed on to King Edward’s Horse gaining his sergeant’s stripes. We have a gold medallion awarded to him (above) while in Australia for being the best shot of the recruits. On his father’s death he came home to manage the estate. A tall man, Edward was 6’ 5” in height. Unlike previous owners he worked on his land. He was often seen at fairs, he ploughed in springtime, he was good with motor bikes and farm machinery. I have here a quote from Philly Creighton whose father worked for Edward : “He (my father) would be minding the cattle and sheep and looking after the ewes and curing them if they got sick. Captain Hornidge himself was a nice man to work for but the wages of course would be very small at that time. However they were very nice gentry people, very decent people to work for.”

The Great War broke out in 1914 and Anglo-Irish gentry were expected to do their bit. Edward offered his services to the Motor Transport Unit of the Army Service Corps on June 9th 1915. Eventually he made it to the 1st Tank Brigade.

He was promoted to the rank of Captain, was mentioned in despatches and came away with an O.B.E. He received his discharge in January 1919 as he had been pronounced medically unfit. Four years before he had damaged his ankle when he fell off a horse. The old injury surfaced again when he was playing rugby and this time he broke the ankle. Nonetheless he was glad to be back in Tulfarris to get on with the spring ploughing. He held 1,300 acres including outside farms and ploughed much of it. A letter from Tulfarris dated 14th March ’19 to Mr Bradley is of interest, of which the following is an excerpt: “Most of the hunts have been stopped by Sinn Feiners out of Dublin on bicycles etc. Punchestown and Fairyhouse are off, much to the annoyance of the farmers, who threaten to collect a pack of mongrels to hunt with and club anyone who tries to stop them.”

Edward had one son, Richard Douglas (Dick) Hornidge. Dick was born in 1915 and was in Tulfarris during the Civil War between the Free State soldiers and the I.R.A. In the U.S. and in his late eighties he took to setting down his memories of growing up in Tulfarris and published them in a booklet entitled ‘Tulfarris’. He had attended Cambridge, like his father before him and he had rowed for Cambridge again as his father had done. Further study in America saw him earning a degree in engineering where he remained for the rest of his life. The I.R.A. often passed through the Hornidge estate on their way to their mountain hideout. Katie the cook would ‘blacken the tay’ when she heard the lorry draw into the yard. With their rifles and bandoliers these were romantic figures in Dick’s young mind. Once he took up one of their rifles and pointed it in their direction, causing general consternation. ‘Plunkett’ O’Boyle led this small detachment of IRA men. In their lorry they would drive in the front entrance and out the back way. They had options which road to take when they left Tulfarris. Later they were confronted by Free State troops in a house up the Wicklow Gap and ‘Plunkett’ was shot dead. His body was returned for interment to his native Donegal. ‘Plunkett’ had tried his hand at writing poetry.

From the Wicklow hills the Staters came

To loot and shoot and win great fame.

With their armoured cars and their Thomson guns

To put the wind up Plunkett’s sons.

And they met McMahon in Ballyknockan Street

And said to him:

You’ve been to France and know the way

So you needn’t be afraid of the IRA.

One Christmas party at Tulfarris Dick still remembered. Tenants and their families were invited. After presents had been distributed and the children felt more at ease a young fellow started playing an Irish Jig on his harmonica. Two young girls glided on to the floor and for the next 10 minutes performed a traditional Irish Jig. Backs perfectly straight, arms unbent at their sides, heads looking straight forward, their entire bodies seemed to float, while they stamped vigorously in time with the music. Dick loved their precision and action. It was as if the children were saying, ‘These dances are part of our heritage and we are proud of them’. Not many years before in nearby Baltiboys Ninette de Valois (Edris Stannus) had had a similar experience with her Irish jig. She was so captivated by it that she claimed learning it started her on her great ballet dancing career.

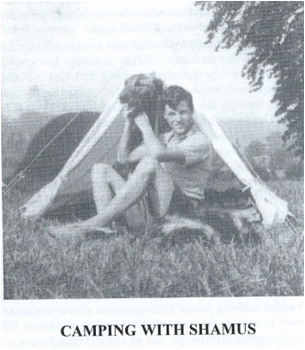

I spoke by telephone to Dick at his home in Andover shortly before his death in 2007. He was ill and confined to bed but talked with animation of his visit here in 1999. He had searched for but had not been able to locate the pet cemetery where his Irish wolfhound Shamus was buried. Shamus’s remains were now, he thought, under a golf green. Dick was the last living Hornidge connection with Tulfarris. He epitomised the dilemma of the Anglo Irish, caught between love of Ireland and loyalty to England. Like many of his family before him he was a great sportsman, proficient in rowing, hockey, skiing, sailing and hiking. Carrying on in the family sporting tradition his son, Richard Jnr, has been a tennis professional.

Edward sold Tulfarris in the year 1947 to the Hamilton family. The lake had taken a large chunk of his land; the Land Commission divided more of it among deserving tenants. The aforementioned Philly Creighton’s father of Kilmalum was one of those to gain outright possession of the 32 acres he had been renting. With a much reduced farm it was not possible for Edward to make a living as he had known it. He had been divorced from his first wife Evelyn Maude of Tinode for some years and married secondly Thelma Stannus, originally of Baltiboys House and sister of Ninette de Valois. The couple moved to County Dublin.

An interesting letter was written when Humphreystown Estate was being sold in the year 1923; the letter refers to an old horse that was ‘out in the Boer War.’ Question is who had the horse down there, and why did it end up in Humphreystown? Unlikely that it would have belonged to Richard Hornidge or Capt. Maude. Perhaps a friend or relation of the Cottons of Humphreystown, or more likely to Thomas Stannus of Baltiboys, whose family left for England in 1905. The owner would have wanted his horse to be well looked after.

Any comments or feedback would be welcome: To contact Jim Corley please click here.